Lots of people embrace compassion, but few embrace effective compassion. What is meant by that? The medical profession provides an easy illustration. The Hippocratic Oath, “first do no harm,” is the ethical guide to the medical profession. It should also govern charity and compassion. But harm is not something we associate with charity and compassion. We think of them as virtues – the more, the better. That view comes from looking at compassion from the aspect of the giver of charity, not the receiver of charity. Or, more precisely, we measure compassion from the giver’s heart, not the receiver’s mind.

The Heart of the Giver

Within the giver’s heart, compassion and charity are very good things. Putting others before ourselves is a “God-like” quality we all admire and strive for. Americans have a strong history of giving to charity and volunteering time. 73% of us donated to charities over the past year and 58% volunteered at a religious institution or other charity (more). As a nation, we spend much on welfare to protect those less fortunate (more). We have one of the most giving cultures ever on the earth.

The Mind of the Receiver

But things get much more complicated when we look at the receiver’s mind. That is where the Hippocratic Oath is measured – on the patient, not the doctor. Is it possible to do more harm than good to the receiver of our charity and compassion?

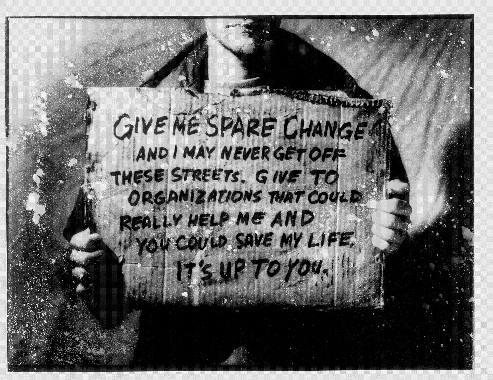

Most experts agree that giving money to a beggar can result in harm. Mike Yankoski describes the problem very well. He wrote a book entitled Under the Overpass. It is a fantastic story. Two college kids lived on the street with no money and no shelter to bring attention to homelessness. They spent five months wandering the streets of six cities living on handouts. They got to know homeless people well – they lived with them. And after all of that, here is how they answer the question, should you give money to beggars[2]:

“Probably not. … we met other homeless men and women whose only income was from money dropped into a hat or cap. Unfortunately, it’s also true that a significant portion of the men and women we knew on the streets would – within a half hour of receiving a donation – spend it entirely on drugs or alcohol. A nugget of marijuana or crack is only five dollars, and a forty-ounce beer is only two-fifty. So your money is probably providing someone with their fix before you even get home or back to the office. That is why I recommend you give them something other than cash.”

Effective Compassion and Poverty

A dollar in a beggar’s cup may violate the Hippocratic Oath, but what about giving to others in poverty? Can we do more harm than good with our charity and welfare programs for those in poverty? Too often, we can. We have to address challenging issues like taking away pride, isolating the poor, and dependency. Too often, we enable bad acts and bad decisions. Not always, but enough, so we have to look at what we are doing with great care and thought.

Robert D. Lupton in his book Toxic Charity summarizes the problem:

“In the United States, there’s a growing scandal that we both refuse to see and actively perpetuate. What Americans avoid facing is that while we are very generous in charitable giving, much of that money is either wasted or actually harms the people it is targeted to help. I don’t say this casually or cavalierly. I have spent over four decades working in inner-city Atlanta and beyond, trying to develop models of urban renewal that are effective and truly serve the poor. There is nothing that brings me more joy than seeing people transitioned out of poverty, or neighborhoods change from being describe as “dangerous’ and “blighted” to being called “thriving” and even ‘successful,’ I have worked with churches, government agencies, entrepreneurs, and armies of volunteers and know from firsthand experience the many ways that “good intentions’ can translate into ineffective care or even harm. [1]”

Real Compassion

When we introduce the Hippocratic Oath to our giving, it changes things rather dramatically. It creates a standard for effective giving. It turns things upside down. Giving money unconditionally is no longer a selfless act but rather a selfish one; done merely to make the giver feel better, not to advance the receiver’s condition. Compassion is no longer enough; effective compassion is required. That is the difference between love and tough love; tough love is much more challenging.

A Handbook on Charity Organization succinctly addresses the issue: “While real charity has a beatitude attached to it, there is no such blessing promised to the man who gives only for the selfish pleasure it affords, the good name it purchases or the annoyance it prevents.” [i]

Ouch! Let’s not do that. We need to adopt effective compassion and know beyond doubt we are genuinely helping others.

This blog supports the Ultimate Guide on How to Help the Poor – Change the Approach

[I] Gurteen, Stephen Humphreys. 1882. “A Handbook on Charity Organization.” Bibliolife, LLC. (Gurteen 1882) page 34.